Daniel Krause on Art, China & the Power of Images

As the north central Regional Resource Librarian at Gensler, one of the world’s largest design and architecture firms, Daniel Krause sees a lot of images. It’s his job to source materials and finishes, and curate spaces — both in the three-dimensional world of built projects and the two-dimensional world of photographs. Despite seeing so much on a daily basis, images still have the power to deeply move him. A trip to the Guggenheim Museum in New York left a lasting and life-changing impression. Daniel — with his friend and colleague D.B. Kim, design director in Gensler’s Shanghai office — recently visited Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World. Here, he shares the experience.

Installation view. Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2017

The Guggenheim gathered works from 71 artists and collectives across China, beginning in 1989, the year of the Tiananmen Square Protests and Massacre, through the Beijing Olympics in 2008. The art brings to life a time of political repression, globalization, individualism and rapid upheaval.

“The exhibition had the effect of recentering me,” Daniel explains. “I’ve gone through lots of ups and downs, and seeing how artists and creative people are able to work through their struggles was very moving. Artists speak in a language that’s accessible to everyone.”

According to the curators, the exhibition explores the role of artists as both “catalysts and skeptics of the massive changes unfolding around them.”

Installation view. Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2017

For Daniel, the show brought up memories of his adolescence in rural Missouri. The youngest of six children, Daniel felt simultaneously connected to his family and drawn to a world beyond his immediate surroundings.

“I would visit my sister in rural Missouri, and look at her magazines — Vogue and Elle — that was my escape,” Daniel recalls. “I remember one summer seeing the cover of Time with the man standing in front of a row of tanks near Tiananmen Square. I had no idea what it was — I wasn’t connected to current events. Years later, that image remains with me and the rest of the world. Art tells the story of what happened.”

Installation view. Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2017

Daniel left his hometown to study interior design. After graduating from Southwest Missouri State, he went to work for several renowned textile and design firms, including Brunschwig & Fils, Cowtan & Tout, Larsen and — eventually — Gensler. Working on projects, including the renovation of PAGODA RED owner Betsy Nathan’s house, Daniel learned how to use Chinese design in the context of modern living.

“We’re only supposed to see China through one lens,” Daniel explains, “unless we’re involved in it. Researching Chinese art and design has opened up my curiosity. As we watch China change, even within all the discomfort, things are very hopeful.”

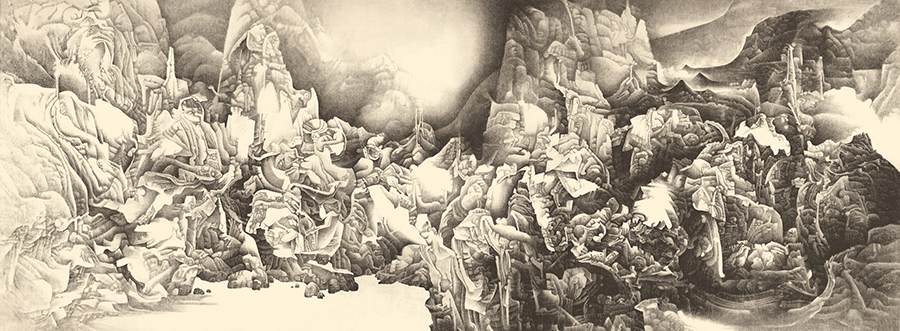

Liu Dan. Splendor of Heaven and Earth. 1994-1995. Ink on paper.

The exhibition embodies the full spectrum of ideas and emotions. As the curators explain, “the artists here have all sought to think beyond China’s political fray and simple East-West dogmas.” Artist Liu Dan, whose intricate ink landscapes contain ancient and modern references, believes that “the clearer the feeling, the blurrier the image.” In other words, art can hold complex cultural ideas and profound feelings in the same space.

“Sometimes our fear of what we don’t know holds us all back,” Daniel says. “Creative people in China are living with real fear — but while their art shares their pain, it also opens up new ways to create and communicate.”

Chen Zhen. Precipitous Parturition. 1999. Bicycles, inner tubes and black plastic cars.

Another favorite piece is Chen Zhen’s Precipitous Parturition, an abstract dragon sculpted from bicycle tires and suspended over the Guggenheim’s atrium.

“The dragon is covered in tiny black cars,” Daniel recalls. “It has to do with the explosion of cars in China, and the transition from bicycles to automobiles brought on by rapid economic growth. The artist took bicycle parts, crumpled them up, and created this amazing analogy for the physical transformation of China’s landscape.”

Ai Weiwei. Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn. 1995. Three black-and-white prints.

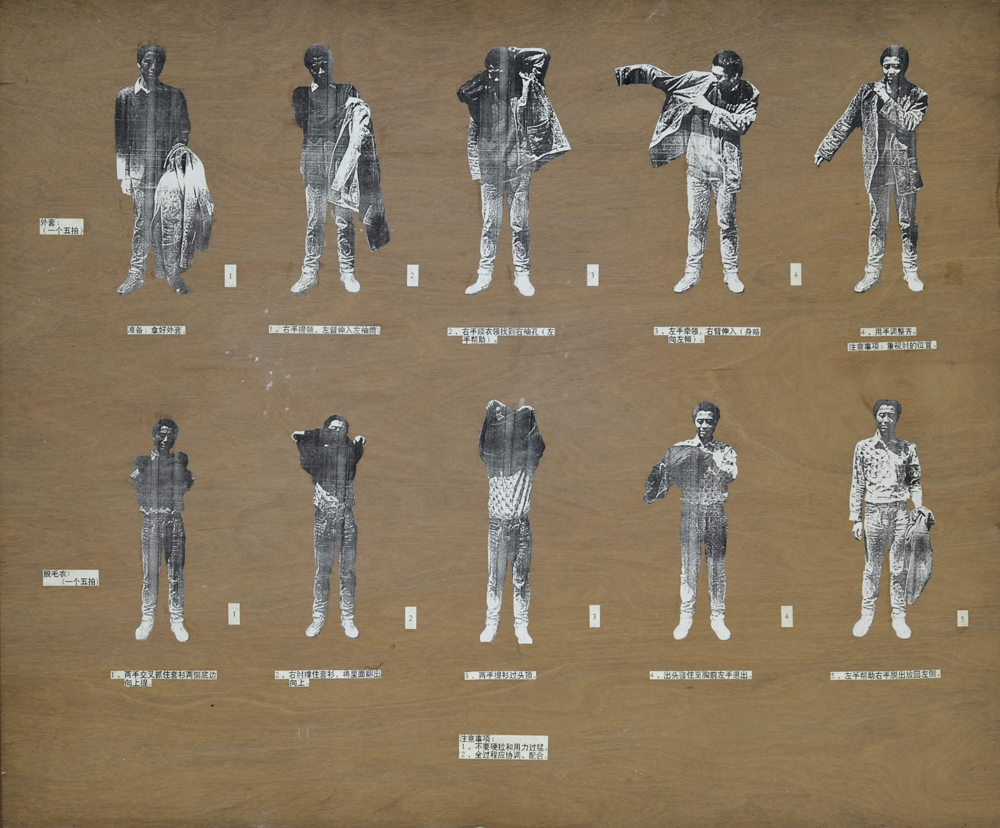

Other notable moments in the exhibition include Ai Weiwei’s Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn — “He’s phenomenal at capturing people’s attention,” Daniel says — and Geng Jianyi’s Two Series of Five Steps of Wearing Clothes, which Daniel describes as “much deeper than what appears.” Rows of photocopied figures in different states of dress explore the tension between individual and collective identities.

Geng Jianyi. Two Series of Five Steps of Wearing Clothes. 1991. Cut and pasted photocopies on wood.

The exhibition is a testament to art’s resonance and relevance, even years after the work is created. It crosses the barriers of culture, time, and language to tell a story without words. As a creator of space and images, Daniel found the exhibition inspiring and applicable to his work.

“Through the power of design, I’m really trying to communicate what people see and experience,” he says. “Gensler believes that this happens through listening, paying attention to people and not forcing something. By being very tolerant of uniqueness and guiding people towards an expression of something real in space and time, we’re trying to make the world better.”

Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World is on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York from October 6, 2017 to January 7, 2018, and the accompanying exhibition catalog includes over 150 works by iconic and lesser-known Chinese artists and collectives. For more information, visit guggenheim.org.

Hero Image:Chen Shaoxiong. 5 Hours. 1993/2006. DSL Collection.

All photos courtesy of Daniel Krause and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.