Book Report: Zen In The Art Of Archery

Zen in the Art of Archery is a legendary book by Eugen Herrigel, first published in Germany in 1948, and in New York, by Pantheon Books, in 1953. The work focusses on the study of Kyūdō, a form of Japanese archery, which the German philosopher pursued in the 1920s, while living in Japan.

Over the years, the iconic book has been released in a numerous editions. Above, a few cover examples.

The tome is widely credited for introducing the concept of Zen Buddhism to the Western world, and inspiring an entire genre of mystical, philosophical books. At PAGODA RED, we consider the history of Asian archers to be uniquely fascinating. Our collection of hand-carved archers’ rings are a perfect window into an ancient practice that is equal parts art form, spirituality, and survival—as in the cases of battle or hunting.

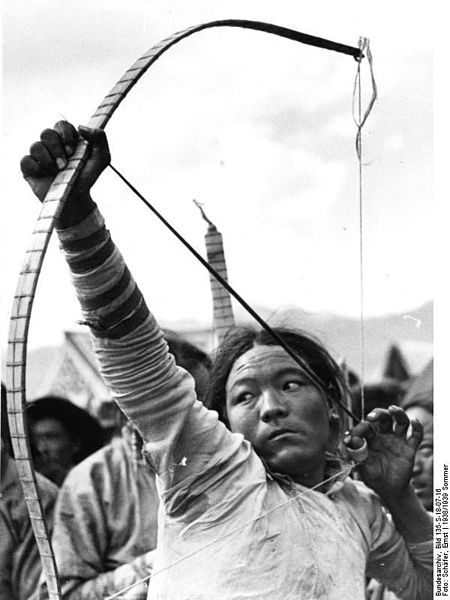

Historically, the substantial rings were used to protect archers’ thumbs from their bow strings, and to supply a precise release action, as demonstrated in the archival image below. But surviving examples have transcended their original utilitarian use, to become wildly-collectible jewelry pieces, and talisman, promising protection, to some.

A Tibetan archer circa 1938, photographed by Ernst Schäfer. Collection of The German Federal Archives.

Similarly, the study and practice of Zen Archery transcends the obvious goal of sinking an arrow into a bullseye. Here are a few of our favorite archers’ rings, along with a selection of quotes from this seminal book.

“Objectively speaking, it would be entirely possible to make one’s way to Zen from any one of the arts,”says Herrigel. “The painter’s instructions might be: spend ten years observing bamboos, become a bamboo yourself, then forget everything and paint.”

Macmillan Publishing says, “In Japan, an art such as archery is not practiced solely for utilitarian purposes such as learning to hit targets. Archery is also meant to train the mind and bring it into contact with the ultimate reality.”

Bone Archer’s Ring | c. 1900 |Dia: 1.25″ H: 1.25″ | Size 13

“It is almost impossible to understand Zen by studying it as you would other intellectual pursuits,” says MacMillan. “The best way to understand Zen is, simply, to Zen. This is what author Eugen Herrigel allows us to do by sharing his own fascinating journey toward a comprehension of this illuminating philosophy.”

The late 19th-century bone archer’s ring above was likely worn by a gentleman-scholar in northern China. By this time, the rings had evolved into fashion accessories connoting status. Those made of rare organic materials such as horn, bone, and unusual gem stones being the most desirable.

“I learned to lose myself so effortlessly in the breathing that I sometimes had the feeling that I myself was not breathing but—strange as it may sound—being breathed,” says Herrigel.

“[Kyudo] consists in the archer aiming at himself—and yet not at himself, in hitting himself—and yet not himself, and thus becoming simultaneously the aimer and the aim, the hitter and the hit,” explains Herrigel, in what sounds like a mystical riddle.

A wealthy gentleman might wear an archers ring, like those pictured above, in the hopes of conveying a level of machismo, he may or may not have actually possessed. Rather than spending years training on horseback, for example, he could simply affect the accouterments of the master archer.

Jade Archer’s Ring Lined in Sterling | c. 1750 | Dia: 1.25″ H: 1.0″ | Size 9

“What stands in your way is that you have a much too willful will,” says Herrigel. “You think that what you not do yourself does not happen… Don’t think of what you have to do, don’t consider how to carry it out! The shot will only go smoothly when it takes the archer himself by surprise.”

The 18th-century archer’s ring above, was hand-carved of the highest quality jade. Dark green in hue with flecks of light, the piece has been lined in sterling silver by a contemporary artisan, to give it a modern finish and narrow the interior to a wearable size 9.

“Perfection is reached when the heart is troubled by no more thought of I and You,” states Herrigal.

Three Japanese archers circa 1860. Photographer unknown. (Image Source: Henry and Nancy Rosin Collection of Early Photography of Japan. Smithsonian Institution.)

In the historic photograph above, Japanese archers in elegant, traditional dress, take aim. It is easy to see the appeal of this age-old practice, and how Herrigal was drawn to its poetry, and the Zen principles behind it.

“The hand that stretches the bow must open like a child’s hand opens, says Herringel. “Man should always act, but he must also let other forces of the universe act in their own due time.”

Jade Archer’s Ring Lined in Sterling | c. 1750 | Dia: 1.25″ H: 1.0″ | Size 9.5

Want to See More?

Located in the Bucktown neighborhood of Chicago, our dynamic 15,000 square-foot gallery is always changing. Storied furniture, fine art and extraordinary objects from around the world are waiting to be discovered. We invite you to experience the spirit of PAGODA RED online or in our gallery.